For global innovators and businesses venturing into China’s dynamic AI landscape, understanding the nuances of patent protection for algorithms is crucial. Unlike jurisdictions with more ambiguous approaches, China employs a distinct and rigorous framework centered on the concept of the “technical solution.” Grasping this core standard is essential for navigating the patentability of AI inventions within the world’s largest patent office.

The Bedrock: Defining a “Technical Solution”

The Chinese Patent Law (Article 2.2) explicitly states that patents are granted for “inventions,” defined as “new technical solutions” relating to products, processes, or improvements thereof. This seemingly simple phrase carries immense weight for AI algorithms. The Chinese Patent Examination Guidelines further elaborate that a “technical solution” must utilize technical means to solve a technical problem and achieve a technical effect.

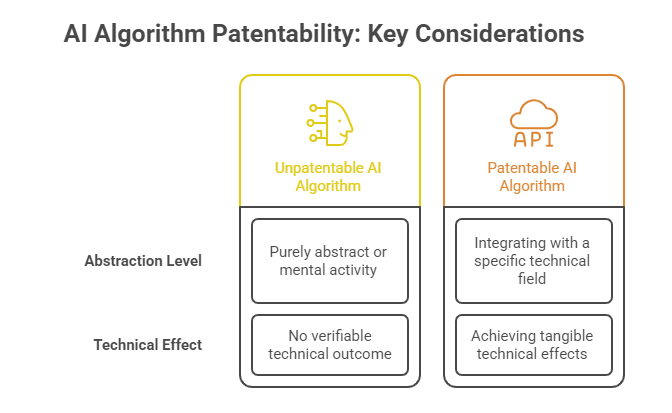

This “Three Technicalities Rule” (Problem, Means, Effect) forms the cornerstone of assessing AI algorithm patentability. Abstract algorithms, mathematical formulas, or purely business methods lacking a concrete technical character typically fall outside patentable subject matter.

Applying the Standard to AI Algorithms: Key Considerations

- Transcending Purely Abstract or Mental Activities: An AI algorithm cannot be patented if it merely performs calculations, data analysis, or decision-making that could theoretically be done by a human mind without technical implementation. For example:

- A basic algorithm solely calculating optimal marketing spend based on historical data (abstract business method) would likely fail.

- An algorithm merely identifying patterns in user behavior without specifying a technical application is likely too abstract.

- Integrating with a Specific Technical Field: Patentability hinges on the algorithm being applied to solve a concrete problem within a recognized technical domain. The algorithm must be more than just software; it must interact with or control physical systems, process technical data in a novel way, or improve the functioning of a specific technological apparatus. Examples that often meet the standard:

- Industrial Control: An AI algorithm optimizing robotic arm movements in real-time for precision manufacturing, reducing error rates and material waste (Technical Problem: Precise control; Means: Algorithm controlling actuators; Effect: Improved accuracy, efficiency).

- Medical Diagnostics: A novel deep learning algorithm analyzing medical imaging scans (like MRI or CT) to automatically detect specific pathologies with higher accuracy and speed than existing methods (Technical Problem: Accurate/fast diagnosis; Means: Algorithm processing image data; Effect: Improved diagnostic outcome).

- Network Optimization: An algorithm dynamically managing network traffic flow in a 5G/6G system to minimize latency and prevent congestion under varying loads (Technical Problem: Network efficiency; Means: Algorithm controlling routing; Effect: Reduced latency, stable bandwidth).

- Autonomous Driving: A computer vision algorithm specifically designed to process LiDAR and camera data fusion in real-time for robust object recognition and collision avoidance (Technical Problem: Safe navigation; Means: Algorithm processing sensor data; Effect: Enhanced safety).

- Achieving Tangible Technical Effects: The algorithm must produce a verifiable technical outcome, not just an economic, managerial, or purely presentational result. The effect should demonstrably improve the functioning of a device, system, or process in the physical world or in the realm of data processing tied to a specific technical context. Examples:

- Valid: Reducing energy consumption in a data center cooling system, improving image resolution in a camera system, enhancing speech recognition accuracy in noisy environments, increasing data transmission reliability in a communication chip.

- Invalid: Merely improving user engagement on a website, optimizing ad placement for higher click-through rates, or categorizing news articles for better readability (unless tied to a specific technical problem like efficient data storage/retrieval in a novel way).

The Evolving Guidance: CNIPA’s Stance

The China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) actively refines its approach. Key points from recent guidelines and practice include:

- Focus on the Whole Claim: Examiners look at the claim as a whole. If the algorithm is claimed as part of a method or apparatus that solves a technical problem using technical means for a technical effect, it can be patentable, even if the algorithm itself involves mathematical steps.

- Data Itself is Not Technical: Claims focused solely on data structures, data itself, or rules for presenting information are generally not patentable. The application of data processing to achieve a technical goal is key.

- “Technical Contribution” Analysis: Even if an algorithm involves non-technical aspects (like business rules), patentability may exist if the algorithm, as a whole, makes a contribution to the technical solution. The non-technical parts must be integrated in a way that produces the required technical effect.

- Clarity and Support: Claims must clearly define the technical features and how the algorithm interacts with them. The description must sufficiently disclose the algorithm’s implementation to achieve the claimed technical effect, often requiring flowcharts, pseudocode, or detailed functional descriptions. Vague or overly broad “black box” algorithm claims face rejection.

Challenges and Strategic Implications for Foreign Applicants

- The “Technical” Threshold: The interpretation of what constitutes a “technical problem,” “technical means,” and “technical effect” can be nuanced and sometimes stricter than in the US or Europe, particularly regarding business method or pure software innovations. What might be considered patentable subject matter elsewhere might not automatically qualify in China.

- Drafting for Success: Crafting claims that clearly articulate the technical context, problem, the specific role of the algorithm as a technical means, and the concrete technical effect is paramount. Generic algorithm descriptions are insufficient.

- Focus Claims: Draft claims that explicitly tie the algorithm to a physical component (sensor, actuator, processor controlling hardware) or a specific technical data processing task (e.g., “A method for denoising medical image data comprising…”, “An autonomous vehicle control system comprising… configured to execute an algorithm for…”).

- Detail the Effect: Provide measurable technical results in the description (e.g., “reduced error rate by X%,” “increased processing speed by Y%,” “improved accuracy by Z units”).

- Avoid Abstract Language: Minimize claims centered solely on input/output relationships without specifying the underlying technical mechanism or application.

- Prior Art Landscape: China has a vast and rapidly growing AI patent database. Conducting thorough prior art searches specifically within Chinese databases is essential to assess novelty and inventive step (non-obviousness) in the local context. What may be novel globally might already be disclosed in a Chinese patent application.

- Inventive Step (Non-Obviousness): Even if a technical solution exists, proving that the algorithm’s specific implementation involves an inventive step over existing technical solutions in the field can be challenging. The combination of algorithm and technical application must be non-obvious to a person skilled in the relevant technical art.

Conclusion: Navigating the Specificity

China offers robust patent protection for AI algorithms, but the gateway is distinctly defined by the “technical solution” standard. Success hinges on demonstrating that the algorithm is not an abstract idea but an integral part of a solution addressing a concrete technical problem within a specific field, utilizing technical means to produce a tangible technical effect. For international businesses, this demands:

- A deep understanding of China’s specific “Three Technicalities” rule.

- Strategic patent drafting explicitly embedding the algorithm within a clear technical context and highlighting the concrete technical outcome.

- Comprehensive prior art searches focused on Chinese sources.

- Careful navigation of the inventive step requirement within the defined technical field.

Mastering these specific requirements is key to securing valuable IP protection for AI innovations in one of the world’s most critical markets. Understanding the technical nuances of your AI’s application within China’s patent framework is the first step towards securing robust protection. For comprehensive insights into intellectual property landscapes, including patentability assessments, explore our comprehensive intellectual property search services.